Contents

With our work on Gendering Surveillance, the Internet Democracy Project hopes to make more concrete the multifaceted ways in which widespread surveillance shapes, and harms, our lives.

At the time of writing this, we start with presenting you with three case studies on this site, examining the intersection of gender and surveillance in a variety of situations. Over time, we hope to further add to these. In addition, we share in a fourth piece some of the theory that has guided our explorations - this provides the broader framework that ties all work on this site together.

In this introduction, I explain in some more detail why we decided to look at surveillance from a gender perspective. Why gendering surveillance?

Let’s take a detour.

1. The Fledgling Fight for the Right to Privacy

Our starting point? An observation: while both government and private surveillance practices seem to be expanding all the time, the fight against indiscriminate surveillance and for greater privacy protections is not making much headway in India.

In fact, it seems to be going in the opposite direction. In July 2015, the government explicitly challenged in the Supreme Court that the right to privacy is a fundamental right in India. The Supreme Court was hearing a variety of petitions protesting the government’s move to make the Aadhaar (India’s Unique ID number) compulsory to avail of various benefits and schemes.

Since 1975, a number of judges in the Supreme Court have read the right to privacy into Article 21 of India’s Constitution, which guarantees the right to liberty. But those were small benches, with only two or three judges, and with their interpretation, they seemed to contradict two earlier judgments, pronounced by larger benches (Bhatia 2015). When the government questioned, in 2015, whether people in India have a fundamental right to privacy at all, the Supreme Court agreed that there were tensions between these two sets of judgments and referred the issue to a five-judge bunch to resolve it. As of January 2017, that bench, which was to address a seemingly pressing constitutional matter, has not been constituted (Bhatia 2017).

What is at issue here here is not so much the validity of the question raised, but, as Usha Ramanathan has pointed out,1 the time at which this is raised. Why does the government explicitly argue that we do NOT have a fundamental right to privacy now, after more than forty years have passed since that first judgment?

Because in the digital age, in the age of Aadhaar and Digital India, of Facebook and Uber and Google, the right to privacy - or its absence - matter like never before.

2. ‘If You’ve Got Nothing to Hide, You’ve Got Nothing to Fear’?

A second observation: important as these concerns might be, in public discourse they continue to be marked mostly by their absence.

With safety and security frequently highlighted as surveillance’s goals, one reason for this void seems to be that the harms of surveillance in the digital age continue to remain too abstract for many people. For most people, the costs they pay for government and corporate surveillance are simply not evident enough. ‘If you’ve got nothing to hide, you’ve got nothing to fear’, they continue to believe. And that is that.

If you really have nothing to hide, that speaks rather poorly about the quality of your inner life - and I am not arguing this merely to be provocative. Experiencing doubt, uncertainty and shame is integral to every person’s growth as a human being; it is what makes us human. By making not having anything to hide a matter of pride, we dampen our growth as a society.

But what is perhaps even more important to highlight is that such arguments also hide from view this: being comfortable with revealing things about yourself often requires privilege. If your own identity and background fits closely within dominant norms - say if you are upper middle class, Hindu upper caste, male and heterosexual in India - you stand far less to lose by revealing details about who you are than if you are a poor, dalit, lesbian woman.

Whether or not you have anything to hide is becoming less and less important in the rhetoric around surveillance, though. Because increasingly the message that indiscriminate surveillance really is to our benefit, is for our own good, seems to also be gaining ground. This is mostly as a consequence of the normalisation of big data driven surveillance. ‘Give us all your data and we will give you… something! For free!’ - that’s basically the adagio of many of the big Internet giants. And increasingly, the government is using a similar discourse: ‘give us your data and we’ll give you government benefits’. Neither is particular interested in guaranteeing the safekeeping of our data. We just have to trust that it will not be misused.

This new thrust of pro-surveillance arguments poses a particular challenge for human rights advocates in developing countries. By advocating for restrictions on surveillance, are we standing in the way of our country’s growth? In India, we see such arguments play out especially in the context of Aadhaar, where the tensions between privacy and big data are overwhelmingly posited as a concern of development. Yet in developing countries as much as anywhere else, we can not overlook that big data can also function as a surveillance mechanism, with all the harms that come with it. Moreover, contrary to what many people believe, anonymising the data does not really resolve these challenges: study upon study has shown that with as little as four fairly simple spatio-temporal data points, the large majority of entries in a database can be de-anonymised, even if the database contains data for hundreds of thousands, even millions of people (see e.g. de Montjoye et al. 2013).

3. Gendering Our Approach

How then to illustrate how deep the harms of surveillance can run?

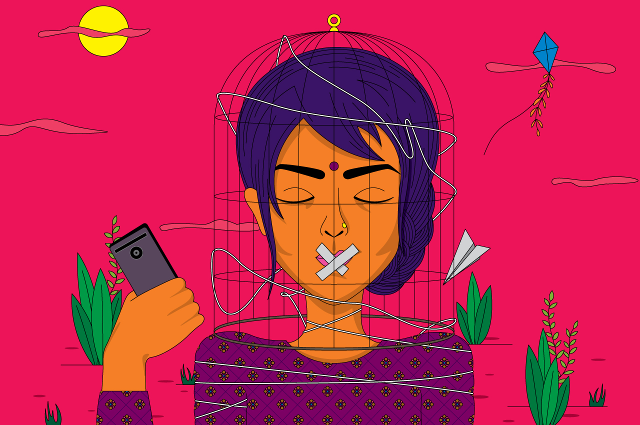

By gendering surveillance, we can really bring home the harms of surveillance. Indeed, surveillance of women is a long-standing practice in our society as elsewhere - and one that women from all castes, classes and religions are too familiar with, even if it affects them differently. As Richa Kaul Padte has argued so poignantly (2014):

The constant and rigorous emphasis placed on the female body in societies across the world tells us two things: One, our bodies are something that we should hide, and paradoxically two, our bodies are something that are constantly on display. The presence of surveillance cameras in public or private spaces – hidden or otherwise – encapsulates this dichotomy perfectly. […] When it comes to spaces that tend to be male-dominated, your crime is the presence of your body, and the camera is, by extension, justified in capturing what you are supposed to hide’.

This is the then the crux of why we chose to look at surveillance from a gender perspective: the aim of surveillance really is to control people, so that everyone adheres as closely as possible to the norm (whatever that norm is). And for centuries, women’s experiences have provided a wealth of information on what happens to those who are surveilled yet deviate from the norm - online abuse targeted at women exemplifies this today again so very well. By gendering surveillance, as we hope the research on this site will illustrate, the depth and range of the harms of surveillance in the digital age, too, can, thus, really be brought to the fore. (And yes, even if you don’t identify as a woman, this does concern you - as one day, it may well be you who is, willingly or unwillingly, found to be violating the norm).

But by gendering surveillance, we do not only get more vivid, easily-relatable illustrations of the harm that surveillance in the digital age entails. In turn, as we will also see elsewhere on this site in detail,2 gendering surveillance also reshapes the debate on surveillance, since it brings to the fore aspects and dimensions that have so far largely remained absent from debates on surveillance and security in India. Gendering surveillance, in other words, both deepens and sharpens the debate, allowing us to move it forward in new, and what we believe are profoundly empowering ways.

Endnotes

1. At the Digital Empowerment Foundation’s Digital Citizen Summit in Bangalore, on 11 November 2016.

2. Want more on why and how? Read ’Reading Surveillance through a Gendered Lens: Some Theory’.

References

Bhatia, Gautam (2015). The right to privacy and the Supreme Court’s referral: Two constitutional questions. Indian Constitutional Law and Philosophy, 11 August, https://indconlawphil.wordpress.com/2015/08/11/the-right-to-privacy-and-the-supreme-courts-referral-two-constitutional-questions/.

Bhatia, Gautam (2017). ‘O brave new world’: The Supreme Court’s evolving doctrine of constitutional evasion. Indian Constitutional Law and Philosophy, 6 January, https://indconlawphil.wordpress.com/2017/01/06/o-brave-new-world-the-supreme-courts-evolving-doctrine-of-constitutional-evasion/.

de Montjoye, Yves-Alexandre, Cesar A. Hidalgo, Michel Verleysen and Vincent D. Blondel (2013). Unique in the Crowd: The Privacy Bounds of Human Mobility. Scientific Reports, 3, http://www.nature.com/articles/srep01376.

Padte, Richa Kaul (2014). The Not-so-strange Feeling that Someone’s Always Watching You. Richa Kaul Padte, 4 September, https://richakaulpadte.com/2014/09/04/the-not-so-strange-feeling-that-someones-always-watching-you/.

Read next

‘Chupke, Chupke’: Going Behind the Mobile Phone Bans in North India

Since 2010, a number of khap panchayats across north India have pronounced bans on mobile phone use for young women. What drives such orders? Are they really effective? And how do young women themselves respond to the bans and the underlying anxieties? We went to Haryana and western UP to find out.

A Handy Guide to Decide How Safe That Safety App Will Really Keep You

Imagine a world where an army of women’s safety apps scoops you away from danger, and delivers you to safety? That’s the promise made by these apps. How well do they measure up against their own claims? Let’s look at a cackle of apps that act as surveillance assistants, leak your data and look smug, while purporting to keep you safe.

Caution! Women at Work: Surveillance in Garments Factories

Garment factory workers, predominantly women, work in stressful conditions in an exploitative industry where the pay is low. Read on to find out what CCTV cameras have done to the dramatic imbalance of power between workers and the factory management, and what role they can play in workers’ fight for an equitable workplace.