Contents

- ‘CC cameras’ at first glance

- 'Your guess is as good as mine'

- Sexual harassment: good cam, bad cam

- The long arm of CCTV cameras

- A culture of surveillance

- Conclusion

- References

If you are in the video surveillance business, there’s no time like the present. Figure this: in addition to the 4,000 CCTV cameras already in place, the Delhi Police has proposed to get 10,000 more cameras at an estimated cost of Rs. 1,225 crores, to make the city safer for women. This is not counting 1.82 lakh cameras already installed by private parties (HT Correspondent 2017). As CCTV cameras become common fixtures in public and privately owned spaces alike, there is an expectation among those installing the cameras, that they will yield new information and insights which were thus far not accessible.

But are the costs justified? There has been mounting criticism on the effectiveness of CCTV cameras in tackling crimes. Studies have shown that CCTV cameras in public spaces are more useful in the aftermath of an incident for gathering evidence, rather than as a deterrent itself, when it comes to serious crimes.

How does this play out in the context of workplace surveillance? In this piece, I report on our investigations into the use of CCTV cameras in garments manufacturing factories in Bangalore, where women constitute more than eighty percent of the workforce, to see in what ways CCTV cameras have changed the space. Who have CCTV cameras empowered, and towards what ends?

1. 'CC cameras’ at first glance

To start with, let’s take a look at how garment factory workers feel about the deployment in their factories of ‘CC cameras’ - a common way of referring to closed circuit television (CCTV) cameras. Opinions, were quite mixed.

Girija, who has worked in different garment factories for the last 17 years, for example, defended CCTV cameras staunchly. She advanced several ways in which they are beneficial for women working in factories:

CC cameras are good and should be there in all factories. Women also benefit from it sometimes. There is theft, teasing, harassment during which CC cameras come of use.

Lots of women sneak in mobile phones and constantly want to talk. How can you work if you talk so much? It is not only for emergency that they talk! Sometimes they go to the bathroom and talk to boys and then get raped. With CC cameras, these things reduce.

To go out, you need a permission slip. If something goes wrong while the women take permission slip and step out, then factories are blamed for it. So factories are correct in taking measures.

Girija was certain that CCTV cameras have enormous potential for enforcing discipline and imbibing good sense in her co-workers.

Meenu, a migrant worker from Orissa was distressed about a post-dated cheque she had received as payment. But CCTV cameras were not high on her list of complaints. ‘Cameras are there,’ she said. ‘ I think it is used to see if we are working properly’. Reflecting the body of literature on workplace surveillance that acknowledges that organisations and monitoring go hand in hand (Ball 2003, 2010), Meenu added that she didn’t find the cameras to be out of place - just necessary.

Still others, like Gowri, a factory worker from the Peenya area, were confident that CCTV cameras are yet another tool of control in the factory. But even Gowri made sure to qualify her remarks to say that it was beneficial to have such cameras elsewhere, like in public places:

CC cameras are good in schools or on the road or in hospitals. But in the factory, it is torture. Even at the main gate it makes sense - so that they can check if anybody is stealing things. But on the floor in the batches, it becomes very hard for us to talk. If we want to talk about work related things like the union also it is hard.

The range of views is unsurprising: as surveillance is usually multi-purposed, it comes with a range of opportunities and disadvantages, which often makes it hard to either support or reject it wholesale (Rosenblat & Kleese & boyd 2014, p. 9).

Spanning from supportive and ambivalent to deeply bothered, garment factory workers’ experiences of being surveilled through CCTV cameras were definitely not homogenous. But it was clear from the get-go that the idea of safety through surveillance had gained a foothold in varying degrees.

Why did some workers have concerns even then?

2. 'Your guess is as good as mine'

Seeing that there is an uptake in CCTV systems in India from the highest rungs of the government to the local coffee shop, it is not surprising that garment factories, competing in a global market for cheap labour, have installed these systems. At three percent unionisation, in an industry where some degree of monitoring is acceptable to workers, resistance to surveillance does not happen at a collective level.

None of the workers remember any advisory or justifications being given before CCTV cameras were installed in their factories, nor did the workers hold any expectations of such communication from their employers. ‘Why do they have to give us reasons?, said Gowri. CCTV cameras have become normalised in factory environments. Anusha, a second-generation garments worker noted, ‘It was there before I joined. Cameras were there in the old factory I worked at also.’

Still, despite the absence of official communication about the purpose of installing CCTV cameras, some workers did hazard a guess. Gowri offered one reason that came up repeatedly in conversations with workers across factories. ‘We have heard from others that it is due to theft,’ she said. ‘Of course the company will want it, it is very useful for them to instill fear in us’.

But Gowri also noted that it is not as if thefts have completely stopped. A raid by the factory owner into a worker’s house revealed about 400 sleeve pieces having been stolen over a period of time. It wasn’t surveillance cameras that helped catch the worker, but a tip-off from a co-worker. Even as the cameras serve to remind workers to not steal, they might not actually be effective in preventing theft. Video surveillance does the job of providing ‘security theater’ more than that of security.

Some estimates from the workers about when CCTV cameras were first installed dated back to 2008, when Ammu, a garment worker, killed herself in a factory bathroom. The suicide note in her palm pegged unbearable persecution by her supervisor as the reason for her decision (Ratnam 2007). Workers who commented on this incident thought CCTV cameras were one of the measures taken by the factories to be seen as doing something in response to widespread protests about deplorable working conditions and increasing factory-related deaths, such as that of Ammu (there were 3 in 2007 alone). Meanwhile, workplace harassment continued unabated, they said.

A third reason for installing CCTV cameras, workers speculated, is to address issues of sexual harassment and safety. Let’s look into that in some more detail.

3. Sexual harassment: good cam, bad cam

Sexual harassment in garment factories is pervasive. As detailed in a June, 2016 report by Sisters for Change and Munnade:

Perpetrators of sexual harassment, because of their supervisory and management roles, have significant power over women workers (with the ability to terminate employment or stop wage payments) and enjoy widespread impunity. 61% of garment workers surveyed indicated that they had been silenced and prevented from reporting cases of sexual harassment and violence by the threats made by perpetrators. And over 1 in 7 women workers said they had left their job due to harassment or violence.

The factories and the brands they supply to have been made aware of these problems. When union members brought up instances of sexual harassment as a regular concern with the HR department of one factory, the HR countered that CCTV cameras have been installed to tackle the problem, and with the cameras in place, there was no room for sexual harassment.

While several workers were convinced that CCTV cameras contribute to their safety and well-being, they were unable to provide any instance where footage from the cameras had proved useful for them to seek redressal. Perhaps their increased sense of safety came more from a belief that incidents might have been prevented- something that is very hard to measure. Contrary to popular imagination, there was proof that CCTV cameras had sometimes been detrimental to fights against sexual harassment, as Usha pointed out:

A complaint of repeated sexual harassment by the supervisor was not taken seriously, thanks to CCTV cameras. The supervisor would come and say lewd things to the worker on the factory floor and provoke her in all kinds of ways, but because the cameras are not able to capture the sound of his words, the exchange did not appear out of the ordinary, and the complaint was dismissed.

Erasure of verbal forms of sexual harassment is a pattern that has been noticed in the context of video surveillance elsewhere too (Koskela 2000).

What’s more, there are plenty of cases where CCTV cameras have enabled new forms of harassment and avenues of voyeurism. Aruna, who heads an NGO that works with garment workers, recalled a case of a supervisor who would ask workers to come half an hour before the start of working hours, in order to solicit sexual favours. The supervisor would do so emboldened by the knowledge that CCTV cameras would be turned on only at the start of the work hours.

This demonstrates two points. First, a ‘displacement effect’: studies on CCTV surveillance have shown that CCTV cameras simply displace criminal activity to areas that are not being watched. This effect has been demonstrated in studies on public surveillance systems where spatial displacements of crime occur. However, it is equally relevant to understand the above case, where a temporal displacement is effected.

Second, an operational knowledge of the workings of the CCTV cameras is powerful to have. The supervisor’s job is in turn surveilled by the management, but his knowledge of when the cameras are switched on enabled him to subvert evidence gathering of his misconduct.

It’s worth mentioning that even extreme forms of violence against women have been known to take place despite the presence of CCTV cameras. In a recent case involving the rape of an employee of a popular IT firm, company officials were quoted as saying they were ‘flabbergasted’ because the incident occurred despite the company having an emergency safety app, ‘panic buttons’ on all buses and cabs and CCTV cameras on its premises (Express News Service 2017). The perpetrator, it turned out, was one of their own security personnel. The official statement from the company reads:

Yesterday’s unfortunate incident is a reminder however that nothing is foolproof, and we are continuing to seek recommendations and suggestions from different stakeholders on how we can try and strengthen the safety of our employees.

Back in the garments industry, a new amendment in the Factories Act 1948 by the Karnataka State government has enabled women to work night shifts from January 2017- something that was only possible so far for workers in the IT and ITES sectors (Express News Service 2016). The amendment is a welcome change for women in manufacturing and service sectors who wish to earn more. Such a move is accompanied by mandatory directions for concomitant safety measures to be put in place. But some union leaders are apprehensive:

We demand proper safety measures with night shifts- in the factory and in transit. Workers don’t take the factory bus if they want to get off at a different stop on their way home to attend union meetings. It is denied. Factory management doesn’t care if safety measures lead to an increase in the worker’s safety or decrease in convenience.

Union leaders hope there will be strong safety measures in place. But they are aware that measures often take the form of restrictive diktats that don’t take women’s decisions into consideration.

CCTV cameras are popular solutions for those forging ‘women’s safety’ agendas, but it can come at great cost to women’s movements and privacy. Whether CCTV cameras are beneficial or detrimental is ultimately determined by specificities and contextual factors like what kind of offences the particular model is designed to capture; who has ownership over the device and the data; and who gets to mobilise it.

The long arm of CCTV cameras

Porous purposes

Supervisors advance CCTV cameras to warn against everything from stealing to wasting time. But the cameras can have unintended effects as well. Women workers complain that CCTV cameras end up making normal, private actions prone to watchfulness, leading to discomfort.

Sometimes we scratch inside our blouses forgetting that there is a camera watching and suddenly it becomes very weird. Nowadays I try to ignore any itch.

As technologies like CCTV cameras become cheaper, they present a tempting opportunity for factory management to deploy them to intrusive levels in the name of increasing efficiency.

They monitor how much time we are in the bathroom. There are watchmen near the bathroom and if we are there for too long in the stall, they will knock. We go there to use our phones but sometimes we get caught. Going to bathroom is monitored from the cameras also.

Moreover, workers have faced real consequences for being caught on camera for actions that aren’t disallowed as such.

Me and my friend were called to the GM room for laughing. He saw it in the CC camera. They cut Rs. 5 for the day from our payment of Rs. 20. It was the first time something happened to me personally. Now we are scared to do anything - even talk. We cannot rest also.

Without a purpose limitation, the ‘function creep’ of the technology enables its use in any number of insidious ways, even if it was not originally intended.

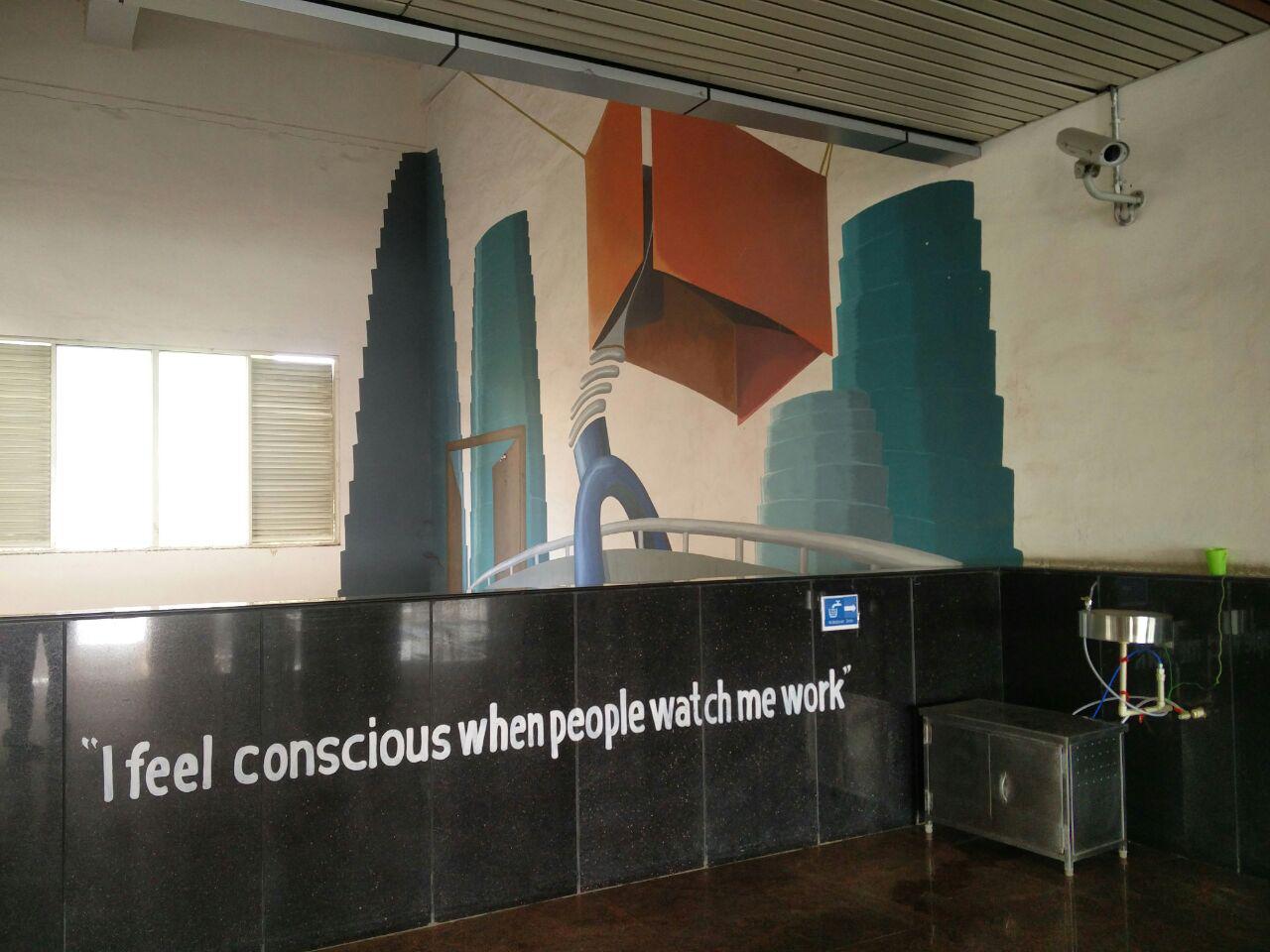

Image: Artwork at the Peenya metro station, Bangalore. (Nayantara Ranganathan, 17 November 2016)

Production targets and surveillance targets

Following from instances of being summoned to the GM’s room, and through supervisors’ threats, workers have figured out that the monitors are located in the General Manager’s room. There is the recognition among some workers that without access to footage and a say in the operation of the cameras, they will merely remain targets of surveillance without any benefits accruing to them.

Only if we are shown the camera will it be useful for us. Even if there is something useful for us, they are capable of deleting it and keeping only what is good for them. If supervisor scolds or tortures or harasses it can be useful. But we have not used it so far. We have used our phones to record videos and use that. That is probably why they don’t like us keeping phones inside.

Mobile phones have proven to be very powerful in the hands of workers. Phones have been used in the past to record evidence of verbal abuse against supervisors and hold them accountable. It is common for factories to require workers to leave mobile phones behind in lockers at the factory entrance before getting to work, and equally common for workers to sneak it in nevertheless.

The empowering use of video footage by factory workers reminds us that CCTV cameras are not undesirable by definition. Power relations need to be examined to assess the value to any technology. Some slums in Delhi and Mumbai (Jha 2013) have installed CCTV cameras with the intention to expose false arrests and persecution by the police of the slum dwellers during episodes of communal violence. Similarly, surveillance cameras might very well prove to be useful for garments factory workers to hold supervisors and the management accountable for certain kinds of actions, if only they get access to the data.

Collective resistance and CCTV cameras

But for the moment, it seems unlikely that that will happen. Unionising is bad for production, and factory managements have many ways of disincentivising workers from joining unions and more generally, from organising to raise their voices against working conditions, including with the help of CCTV cameras.

For example, Hema, a new member of the union, but a long-time ‘loudmouth’ by her own admission, faced punitive action for standing up for her friend when the supervisor spoke to the latter brashly for not staying back for ‘overtime’ (OT) work. The punishment (and a form of deterrent) for her behaviour was to put her on a place on the shopfloor where CCTV cameras could demonstrably focus on her. She admits that this has indeed impacted her morale.

I feel really bad that no one talks to me. I am asked to sit far away from the others. They turn the cameras to point at me so that they can keep me under observation and make sure that I don’t have anybody to talk to.

It is very common for women who talk back in factories to be vindictively targeted with surveillance cameras, and isolated them from their co-workers, confirmed Malathi, a labour union activist and former garments worker.

And there are more shocking incidents of civil and political rights of workers being violated. In April 2016, workers protested against an amendment to the Employees Provident Funds and Miscellaneous Provisions Act, 1952, which would bring a host of restrictions for withdrawal from employees’ Provident Fund. The police cooperated with the factory management to use public CCTV cameras to identify protesters from each factory. Data from surveillance cameras installed at traffic signals by the government were shared with factory owners to zero down on ‘troublemakers’. A fact finding report by the Karnataka People’s Union for Civil Liberties and Women Against Sexual Violence and State Repression- Karnataka confirms that CCTV footage was used in making arrests. Ever since that incident, workers do not linger around outside the gates, said Malathi.

Despite clearly objectionable uses that they are put to, new technologies deployed by employers in exploitative industries don’t get the kind of attention from grassroot labour rights movements that they deserve. Surveillance technologies when used unreasonably and unilaterally, can have real impacts on human rights and the dignity of labour in workplaces. The National People’s Tribunal for living wages and decent working conditions of garment workers, was held in its third edition in 2011. One of the recommendations made by worker representatives to a jury composed of labour rights experts, was to consider the effects of the practice of affixing CCTV cameras to monitor workers in factories. This recommendation was not included in the final jury verdict (Clean Clothes Campaign 2012).

Without specific policy formulations that set out the purpose and scope of surveillance, it becomes hard for workers to locate or question the legitimacy of CCTV cameras. For the same reason, there is no room for distribution of gains from the surveillance between employers and employees. Asymmetries of power are further exacerbated due to the limited technical understanding of the technologies and consequences of their use by workers, and the drastically higher knowledge capital at the disposal of the employer. In the absence of ownership and access to both devices and data, unreasonable surveillance over workers through CCTV cameras becomes normalised.

5. A culture of surveillance

To be sure, a culture of surveillance has existed in garments factories even before CCTV cameras came along. Employees are encouraged to keep a check on their colleagues informally and by way of policies. For example, in one factory, workers are divided into groups of 50. If more than 3 workers take a day off in a month, then the ‘attendance bonus’ for all workers in the group gets cancelled. Workers are incentivised with the reward of an attendance bonus to keep each other answerable. Because taking a day off affects the attendance bonus of everyone in the group, workers are driven to evaluate the necessity and urgency of their groupmates’ private decisions to take off from work. In this way, surveillance is carried out dispersedly, through social burdens of shared penalties.

Migrant workers living in hostels provided by the factories also face a high degree of surveillance when it comes to their movements. They get a window of two to four hours on Sundays when they can leave their hostels to get supplies. A report in qz.com, on prison-like conditions of these hostels quotes one migrant worker as saying ‘ lot of things happen, but we cannot talk about it’ (Bain 2016).

Kirstie Ball (2010) highlights how organisations use a raft of surveillance techniques that are embedded not only within specific tools, but also within the social processes of managing. Surveillance in the workplace, therefore, not only produces measurable outcomes in terms of targets met or service levels delivered; it also produces particular cultures which regulate performance, behaviours and personal characteristics in a more subtle way.

A culture of surveillance played out in our research interactions as well. Focus group discussions for this research were conducted within a safe space, where the workers were willing to speak frankly about the issues they faced. Even when approached near the streets leading to their factories at the end of the work day or in public view during street plays, most workers were happy to open up about their opinions on CCTV cameras. However, unexpected entry of co-workers into the conversations would lead to an unwillingness to discuss the matter further, or a retelling of the issue with milder criticism. The fear of being identified and facing retribution from the management was evident in their sudden hesitations.

6. Conclusion

CCTV cameras are presented as a neutral, apolitical solution which is applicable across spaces, contexts and issues, bringing technological muscle where action is needed. A safety measure for every occasion! But underlying these cameras, like any technology, are interrelationships encompassing devices, bodies, agents, forces and networks (Critical Engineering Manifesto 2011). When CCTV cameras are not deployed in a balanced way, with the consultation of all affected parties, and after a true assessment of the trade-offs involved, they can work to merely polarise existing unequal social orders. What questions then, should we be asking of well intentioned policy makers, in the government and in private enterprises?

(March 1, Update: The article previously mentioned that CCTV cameras had been quoted as a measure to tackle sexual harassment by a factory in multistakeholder meetings. The exchange did not happen in a multistakeholder meeting, but in a meeting with union members in the factory itself. The article has been changed to reflect this.)

(I interviewed key informants from Garment Labour Union, a women-led, women-centric labour union in Bangalore. Between November and December, I conducted interviews and focus group discussions with women and men employed in garment factories in the areas of Peenya and Mysore Road in Bangalore. I reached out to the concerned factories for interviews, but my requests were declined. All names used in the article are fictitious, to protect the identity of the interviewees. I’m grateful to Cividep, Garment Labour Union and Ms. Anita Cheria for facilitating interviews and discussions and the garment factory workers for sharing their stories.)

References

Bain, Marc (2016). “We cannot talk about it”: Factory workers for major fashion labels live confined by guards. Quartz, 29 January. https://qz.com/605914/we-cannot-talk-about-it-factory-workers-for-hm-and-others-live-confined-by-guards/

Clean Clothes Campaign, (2012). Human Rights Trial on Garment Industry Concludes. Clean Clothes Campaign, 24 November. https://cleanclothes.org/news/2012/11/24/human-rights-trial-on-garment-industry-concludes

Express News Service (2016). Government Removes Night Shift Curbs for Women. Indian Express, 23 December. http://www.newindianexpress.com/cities/bengaluru/2016/dec/23/government-removes-night-shift-curbs-for-women-1552212.html

Express News Service (2017). CCTV Footage Given to Police Following Rape Incident at Pune Infosys. Indian Express, 12 January. http://www.newindianexpress.com/cities/bengaluru/2017/jan/31/cctv-footage-given-to-police-following-rape-incident-at-pune-infosys-1565327.html

Jha, Nishita (2013). Someone's Watching You, But Who? Tehelka. 16 November. http://www.tehelka.com/2013/11/someones-watching-you-but-who/

Koskela, Hille (2000). 'The Gaze without Eyes': Video-surveillance and the Changing Nature of Urban Space. Progress in Human Geography, 24(2): 243-265.

HT Correspondent (2017). Delhi Police Plans to Buy 10,000 CCTV Cameras Using 1000 Crore Nirbhaya Fund to Safeguard City. Hindustan Times, 19 February. http://www.hindustantimes.com/delhi/delhi-police-plans-to-buy-10-000-cctv-cameras-using-1000-cr-nirbhaya-fund-to-safeguard-city/story-aQ845cdaIJ7euZxqkbJKSL.html

Oliver & Savičić & Vasiliev (2011). Critical Engineering Manifesto. The Critical Engineering Working Group, October. https://criticalengineering.org/

People’s Union of Civil Liberties and Women Against Sexual Violence and State Repression (2016). Bangalore Garment Workers’ Protest Demonstration: A Preliminary Fact-finding Report. Karnataka: People’s Union of Civil Liberties and Women Against Sexual Violence and State Repression. http://sanhati.com/blog/17090/

Ratnam, Anita (2007). Ammu’s Death Strips Garment Industry of All Halo. Deccan Herald, 8 March. http://archive.deccanherald.com/Deccanherald/mar82007/panorama0519200738.asp

Rosenblat, Alex, Tamara Kneese and danah boyd (2014). Workplace Surveillance. Data & Society Working Paper, Data & Society Institute, New York, 8 October. https://datasociety.net/pubs/fow/WorkplaceSurveillance.pdf

Sisters For Change and Munnade (2016). Eliminating Violence Against Women At Work: Making Sexual Harassment Laws Real for Karnataka’s Women Garment Workers. UK: Sisters for Change. http://sistersforchange.org.uk/india-eliminating-violence-against-women-at-work/

Read next

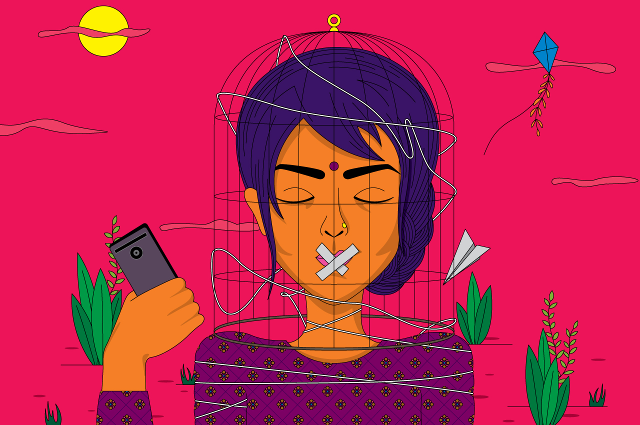

‘Chupke, Chupke’: Going Behind the Mobile Phone Bans in North India

Since 2010, a number of khap panchayats across north India have pronounced bans on mobile phone use for young women. What drives such orders? Are they really effective? And how do young women themselves respond to the bans and the underlying anxieties? We went to Haryana and western UP to find out.

A Handy Guide to Decide How Safe That Safety App Will Really Keep You

Imagine a world where an army of women’s safety apps scoops you away from danger, and delivers you to safety? That’s the promise made by these apps. How well do they measure up against their own claims? Let’s look at a cackle of apps that act as surveillance assistants, leak your data and look smug, while purporting to keep you safe.